So many of the examples in this essay are pure coincidence. I swear I did not have to reach far for any of the examples. Each is just the first thing that was given to me when I was looking for concrete corroboration for my opinions.

Today “faking” is practiced as a substitute for a sound musical education, to fool the ears of a passive audience who are gagged on cultural junk and dispensing with the need for musicians to practice their craft on a fully informed basis. But in the historical common practice period 1450-1950, the ultimate in improvisation inverted this phony faking — called “figured bass”, it reposed on an extremely sound musical education, bordering on the art of composition, as with Albinoni’s Adagio in G Minor, a dramatically moving experience fully fleshed out upon a mere fragment of figured bass.

Shortcut to this page: wp.me/p256FR-nZ (case sensitive)

A century ago, virtually everyone sang, on a frequent basis, in their personal, social, cultural lives. And now, almost no one sings with any regularity. What is the effect of that cultural lapse upon the worship habits of Christians?

Before radio (1923), if you wanted music, you had to make it yourself. This fundamental fact, sharply divides us from all previous history. People 100 years ago and beyond, frequently sang. People today don’t generally sing, at all.A century ago, and beyond into the remote past, a much higher quality of music was sung in church services by churchgoers and choirs. Congregations were not passive consumers of service music, as singers they were much more active participants than today, in their church music, and indeed, in all the music of their lives, as the primary singers of music they loved. And church choirs were not limited to the inane, insipid music fare so many congregations tolerate today. Their service music came from hymnals of high quality, multi-part arrangements of well-established little classics.

Our great-grandparents all sang just like this.

Our contemporaries haven’t the slightest idea that this was once the standard religious culture.

Our choirs once regularly practiced robust choral harmony. But this full harmony has disappeared, in a substantial part as an unintended consequence of the practice of Faking in today’s church music.

Faking is customarily playing from a chart (outline), as opposed to performance of sheet music, using streamlined keyboard “improvisation” as the musical standard, bypassing explicitly composed 4-part vocal harmony, along with overly-simplistic guitar playing.

The current faking church music practice tends to reinforce the broader, general trend toward relegating congregations to the status of permanent spectators in worship, there mainly to hear a “performance” rather than more directly, personally worshiping God in spirit and in truth with burning hearts and full-throated voices.

Prior to the 1960s, congregations had long, routinely brought to their worship a vigorous home song-culture – unknown to today’s techno-media consumers. The ordinary, common people were possessed of a surprisingly high average culture level, based on primary education that looked for its model to the Christian acceptance of the classics of Western civilization.* *Anthony Esolen notes the history of a Manitoba wheat farmer who would recite Milton’s “Paradise Lost”, from memory, as he performed his manual-labor farm work, a real-life example of Ray Bradbury‘s, Fahrenheit 451 Book People.

Very few in the congregations are even singing at all. Once, they nearly all sang.From a century past, back into remotest history, the common people brought with them to church, an active, personal singing pastime. They had the customary, frequent habit of singing popular, folk and classically-informed home music. They took this robust “middlebrow” culture to their church congregations to sing worship music of a high level of artistry, not just letting a few isolated soloists, often of modest ability, exclusively produce the music–often in a degraded form. Nowadays the standard of church music is faking, under which musicians often with little educated background take the solo spotlight instead of leading congregations themselves in singing out. Under this regime, very few in the congregations are even singing at all. These conditions are based upon the cultural impoverishment of the era of canned-music in which people have stopped their natural daily cultural exercise of singing just for the pleasure of it in their personal lives.

Do you sing at home? ^Top

What, Actually, Is Faking? – Radical Individualism Crowding Out Group, Congregational Singing.

The facts about what faking is and how radically it has debilitated our musical culture can be gleaned from the example below.

“Abide With Me” Faked (music video): The faking chart typically lacks alto, tenor or bass; it only has chords, single melody line and lyrics. The faking performance linked to here is of a good quality; the performer has put some work into the arrangement. But it isn’t truly a “spontaneous improvisation”, it’s “worked-out” as much as if it were a written-out, permanent arrangement. The traditional bass line is largely followed, the traditional sense of the harmonic outlines is acknowledged if not strictly adhered to. (Yet cutting corners on traditional bass lines is one of the chief foibles to which ordinary faking performances are prone.) But even a high-quality faked performance pulls the rug out from under any choristers or congregation members who would wish to follow the traditional arrangement, because the various inner parts can receive no support, but only suffer contradiction by the “improvisation”, as the soloist assumes greater prominence than the choir or the congregation. “Abide With Me” Unfaked (music video).

Unlike personal prayer, church worship is inherently a group activity. “When we stand, we stand together; when we fall, we fall alone”, an Orthodox Christian maxim puts it. “Not forsaking the assembling of ourselves together, as the manner of some is; but exhorting one another: and so much the more, as ye see the day approaching.” – Hebrews 10:25. The hymn, Abide With Me (lyrics), is precisely about the Lord not abandoning us, not to be left alone, so that the enemy of souls can’t get at us.

The radical individualism of Faking pits the soloist as “star” against the social, group context of church music.

The God-created nature of worship music is to be a group activity. “Let the word of Christ dwell in you richly in all wisdom; teaching and admonishing one another in psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, singing with grace in your hearts to the Lord.” – Col 3:16. Singing prayer is the norm in Christian worship. Among the best forms of worship are those centered on music. “Those who sing well, pray twice”, says Augustine.

But the highly personal, interpretive faking performance tends toward radical individualism, pitting the soloist as “star” against the basic group nature of singing. Keyboard faking inherently tends only to allow the choir to sing the melody line in unison, interfering with the harmony which multiple singers should be able to perform together.

We’re so used to music made with faking, that it doesn’t occur to us to note the distinction between faking and historical multi-part harmony. Without this awareness, we can’t discern the disadvantages of inferior contemporary “faking” keyboard practice and 3-chord twanging. And since we aren’t very active singers, we don’t know much from our own experience how our church services have suffered disadvantages from adverse changes to music in the past 50 years.

But we have suffered a loss of quality in our musical lives, since we stopped singing, and since informal keyboard and low quality guitar playing have assumed control of our church music. Fine, vigorous and sometimes ornate old traditions, not stodgy and boring as it was claimed in the early days of contemporary music, were shunted aside, with little consideration for the consequences. But an acute look back at what has been lost, tells the true story of how little has been gained by the new music. ^Top

The Dominance of Music in Worship – the Trend Parallel to Cinema Music

What’s so important about the music that we hear in church? Well, for one thing, it’s really the only context almost any of us has to be able to sing live music in a social setting. And there, music largely sets the tone for everything else that occurs in church services, as it also does in the cinema, the second most common context for the social appreciation of music. (A once highly, personally interactive environment, worship in church, has in many instances been technologically reduced to a mere “multi-media” consumerist shadow of active culture.)

When Ray Milland threatened on-screen to commit suicide, audiences laughed.Test audiences laughed at what should have been a highly dramatic moment in The Lost Weekend (1945), during protagonist Ray Milland’s suicide-attempt scene, in which Jane Wyman wrestled him for a gun. (A decade after William Powell and Myrna Loy, as “Nick and Nora” in Dashiell Hammett’s The Thin Man (1934) had made excessive alcohol-consumption an object of humor verging into the ridiculous, new ground was broken by The Lost Weekend in seriously addressing the topic of alcoholism.) Once the dramatic production was nearing completion, at test audience showings immediately preceding final editing, the last thing producers wanted was for people to be laughing at one of the film’s crisis scenes.

Europe-trained film composer Miklos Rozsa was brought in to save the film production from what amounted to disaster, with the application of a professional music score in the light-classic genre that would accord with the expectations of audiences of that day. After Rozsa’s intervention, “The Lost Weekend” went on receive seven Academy Award nominations and to win four – including Best Picture, Best Director and Best Actor – as well as the first Cannes Film Festival Grand Prix.

Europe-trained film composer Miklos Rozsa was brought in to save the film production from what amounted to disaster, with the application of a professional music score in the light-classic genre that would accord with the expectations of audiences of that day. After Rozsa’s intervention, “The Lost Weekend” went on receive seven Academy Award nominations and to win four – including Best Picture, Best Director and Best Actor – as well as the first Cannes Film Festival Grand Prix.

The overwhelming primacy of the element of music in cinema, bears witness to the parallel importance of music in the worship environment. Rather than a fluke, the dominance of music in cinema is the norm, in terms of setting the emotional tone, to reverse the normal precedence, almost as if the visual component of cinema is secondary accompaniment to primacy of the music score.

Sergio Leone intentionally left space for the music to be listened to and adapted his camera movements to its sounds. – Ennio Morricone

This is shown by the career history of the dean of golden-age Hollywood film composers, Max Steiner. Brought in to salvage King Kong (1933), a film that was likely to fail until he was engaged to supply the music, Steiner led Kong on to garner worldwide rentals of nearly $3 million and profits of $1.3 million (the equivalent of $18 million today) at a time when it cost 25¢ to go to the movies, a successful run for the time.

For the 1939 Gone With the Wind, Steiner defied David O. Selznick’s direction to use existing classical music, independently composing more than 3 hours of original film music and hiring an 80-piece orchestra on his own recognizance. (No other division of the film production process would have ever enjoyed such independence from the normal budgetary oversight obligatory upon all production divisions.)

Steiner went on to win the Academy Award for Best Music, Original Score, one of 10 Oscars garnered by Gone With the Wind. Counterintuitively, it might be argued that the single most important member of a motion picture’s creative team is not, the lead actor, the script playwright, the producer or the director –but, rather the, film score composer.

In view of the tendency of music to dominate church services at a similar level of intensity as that which the history of cinema records, Pastors and church elders would be well commended if they were to keep greater control over what the casual musicians play, rather than letting them conduct the proceedings so largely on their own. Faking and poor guitar music are the standard for musicians who have taken over so much of our worship.

In view of the tendency of music to dominate church services at a similar level of intensity as that which the history of cinema records, Pastors and church elders would be well commended if they were to keep greater control over what the casual musicians play, rather than letting them conduct the proceedings so largely on their own. Faking and poor guitar music are the standard for musicians who have taken over so much of our worship.

^Top

FAKING – Throwing Out Tradition to What Benefit?

Church musicians’ “progressive music” may bear little resemblance to the congregation’s actual musical preferences.What happens when music superstars are allowed to run our worship services? Today’s standard worship music practice would be typified by the actions of the pianist-leader of a competent Filipino choir at a local congregation, in which all the members harmonize quite adequately. On a Sunday last year, the pianist applied fake marks to a traditional four-part arrangement of a hymn, for playing in a streamlined style which many church musicians would imagine to be progressive–but possibly bearing little resemblance to the congregation’s actual musical preferences. (Untypically, that Filipino choir sang harmony to the keyboard faking, the vigorous choral life of their home, cultural heritage having fortified them. But most choirs can’t harmonize to keyboard faking.)

Faking isn’t an inherently deprecatory term, in its proper place it is the standard musical designation for the fine art of extemporaneously improvising a usable performance from the scanty materials of only the lead melody line, chord names and lyrics, dispensing with sight-readable music text for the other parts, reducing the total sung performance to only the unison, melody line, cutting out any autonomous, vocal harmony. Faking should properly be used only under special, emergency-demand, usually when the players receive a last-minute request for an unplanned piece––in which case a certain looseness of interpretation and faultiness of execution can be overlooked. But faking should not be used as the standard, pre-planned foundation for regular worship music performance. The true, red-blooded harmonic tradition of the common-practice period 1450-1950, had long already been enriched by an educated form of “faking”, known properly as figured bass, as with the Adagio in G minor, attributed to Albinoni, but actually based only on a fragment of figured bass. Practitioners of figured bass were known to practice the art of improvisation to hone it to perfection––the opposite of what churchgoers have to expect every Sunday.

I recovered that player’s fake sheet from the trash, removed the fake marks, refactoring it back to traditional four-part arrangement. The congregation later sang to my rendition of the traditional four-part arrangement of Lord Who Throughout These Forty Days during a worship service.

The common practice of using faking as the permanent, regular basis for choral support, serves actually to cripple choirs’ ability to practice harmonization. Faking’s severe reduction of our once common, intricate harmonic virtuosity, undercuts choirs’ ability to learn the basic musicianship of harmony–most choirs never even get to hear real, four-part vocal harmony, much less to begin to practice it.

An inherent limitation of improvisation is that it is experimental. In performance situations which require a definitively assured overall composition schema, a ruling canon, an authoritative 10 Commandments of musical notes, any temporary improvisation risks a certain rate of failure of conception; and the extent of error can be magnified when the improvisor’s execution also suffers a mistake. Worship music cannot tolerate failure in the experimental conception or execution. The most masterful musicians, such as Mozart and Bach, pushed to an extreme the implicit tension between authority and innovation, so that the players may at first fail to comprehend the overall, integral intention of their compositions. That is why hymnals rely heavily on established masterworks based on the background of improvisatory experimentation which has been thoroughly vetted for inerrancy, and the live-time execution of that authoritative interpretation practiced to perfection.

Prior to the 1960s, organists customarily, exclusively played from four-part arrangements, supporting choirs in their group practice of vocal harmony. (When the choir sings without the congregation, then acapella, voice-only performance without the organ is the ideal; but during the majority of the service when the congregation should be singing in their worship practice, the organ is indispensable.)

Four-part arrangements, intimately linking keyboard practice with vocal harmony, are the total content of most pieces in keyboard hymnals. The organist plays exactly what each of the individual four parts sing together–soprano, alto, tenor and bass. The choristers receive organ support in their quest for attaining mastery of the pieces, singing each of their parts together from the grownup, 4-part, keyboard hymnal.

Multi-part, “traditional” harmony choirs are not restricted to a kindergarten-crayon level as perpetual beginners using the single-line “melody edition”, only allowed to sing the simple melody in unison without the harmony, as enforced by faking.Traditional harmonic choir singers are not restricted to a kindergarten-crayon level as perpetual beginners using the single-line melody edition , only allowed to sing the simple melody in unison without the harmony, a de facto restriction on vocal practice enforced by the very nature of keyboard faking.

In proper practice, in high-church and evangelical traditions alike, the organist’s playing serves as a lattice for the singers’ accurate performance of classic hymn pieces, ideally composed from a vocal rather than keyboard perspective, minor masterpieces often composed by major classical composers, a lay cameo of high art music.

Under the tyranny of faking undercutting four-part harmony, the only accompaniment most choirs ever get to hear is homogenized, plain-Jane vanilla fill-in chords of oversimplified harmonic rhythm. The music may be electronically augmented, but beneath the glitz it can be quite impoverished, performed under the restricted regime of bare-bones, chords-melody-&-lyrics, accompanied by low-grade, standardized keyboard “riffs”, dead, background props which involve very little improvisatory innovation. The limited technique of the faked accompaniment of hazy, opaque playing, even many educated listeners fail to notice, exactly as intended. “It’s easy to fake; they’ll never notice the difference.”

If today’s self-avowed music specialists were capable of performing an advanced extension of the full common practice period culture into their envisioned, modern milieu, as implied by their presumptuous, customary employment of faking, they would necessarily be fully musically literate, maintaining a high pitch of sight reading practice of multi-part scores, with active working knowledge of theory, form & analysis, and music history. The opposite condition is what actually prevails–by and large they have thrown out that legacy as insufferably academic, curiosities of indifferent value to be relegated to the dusty smell of a mausoleum-museum.

Keyboard faking chordal fillin interferes with singers’ harmonic overtone blending, ruining the succulent relish of singers carefully modulating their harmonic overtones.Wallpaper fill-in of keyboard faking accompaniment is corrosive of vocal harmony. Singers’ blending is based on fundamental acoustic properties of interacting musical tones in triadic harmony, the consonance or dissonance of overtones in the harmonic series between singers’ interacting tones, singers regulating difference-tone beating between pure harmonic consonances and deliberate, mild dissonances. (The same property fundamentally affects the interaction with guide drone tones in the microtonal intonation of Eastern melismatic music. In the West, only vocal, unfretted string and brass music convey this attribute fundamental to the essential art of music; other instruments fail to convey it; keyboard-fake music is the most remote from harmony.)

In the West, only vocal, unfretted string and brass music convey the harmonic-overtone blending attribute fundamental to the essential art of music; other instruments fail to convey it; keyboard-fake music is the most remote from harmony.The deliberate indistinctness or fuzzyness of keyboard fill-in is antagonistic to the acute, succulent relish of Western singers’ carefully modulating their harmonically interacting overtones. (I mean to signify first world, Western culture, not the Country and Western music genre.) Keyboard faking fill-in is oriented towards indistinctness, a wallpaper background to highlight the unison melody line. The sweet-savory sound of singers’ harmonic blending is the opposite, not towards lack of distinction, but keeping in sharp focus. Left on their own without faking interference, harmonic singers raise the hair on the back of heads, their own and audiences’. Keyboard faking, muddying harmonic blending, is fundamentally antagonistic to vocal harmony.

Ethnomusicologist Curt Sachs speculated that the crinkled foreheads of angels on the Ghent Altarpiece accurately reflected the singers’ practice of modulating vocal timbre, flaring nostrils and opening the pharyngeal palate, evoking interior head-space resonances, deliberate nasality in common between Appalachian tradition and ancient European music, to amplify the interaction of specific overtones in emphasis of the relish of harmonic singing, as the Quebe Sisters do in their performance above–sort-of a cross between Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys, and the Andrews Sisters.

Many choirs suffering under the regime of faking, deprived of harmony experience, cannot even abide the occasional singing of harmony in their presence, of any kind! If one singer starts harmonizing ex tempore or from the memory of fine traditional arrangements, other, more-nearly average choir singers will tend to falter in their execution of the main melody, often ceasing singing altogether, because they find the unfamiliarity of vocal harmonization radically distracting. (The poverty of their musical education and lack of exposure to more cultivated music leaves them lucky even to be able to carry just the unison melody. Harmony stops them.) This is the current norm, under cover of keyboard faking and enforced unison singing. The pianist isn’t playing a four-part arrangement to support the singers; how can they sing in harmony, despite the faking?Average choir singers get thrown-off by hearing harmony; they frequently stop singing altogether.

The usual reason given for neglecting to train choirs for singing with other singers who are harmonizing, is the claim that “it’s too hard for them”. This claim is contradicted by the historical fact that the practice of harmonization was the norm in even the most informal ensembles in past ages, from even just a few decades before the 1960s cultural revolution. “It’s too hard” for today’s choirs only because the players haven’t been exposed to it. “They can’t sing with harmony because…well, because they can’t sing it” is a “just ‘cuz” excuse–an illogical, self-referential, circular argument. ^Top

In Search of the Lost Chord – A Vital Cultural Tradition Gone Down to Demise

A group of old duffers sitting around casually, spontaneously singing multi-part harmony, as virtually everyone did except the tone-deaf, at home, in taverns and other social spaces, true “spontaneous improvisation” without the cultural “faking”.

A very common sentiment is for people to proclaim “I love music”. But today, that love is passive, the love of mere spectators, tourists to life, just passing through, only here to be “short-timers”. A century ago, the love of music was active, the love of singers, those who lived song. Everyday singing was the default cultural condition, a widespread social habit more ingrained than just a hobby, a full dimension of interpersonal life completely atrophied today, but at that time casually practiced by nearly everyone. An accurate picture of our near-ancestors’ daily musical lives can be gleaned even through commercialized Hollywood film productions.

Singing Prize that Solved a Murder – O. Henry’s “Clarion Call” from the movie “Full House” (1952). Richard Widmark could presume that a chance stranger, a bartender, would be able to sing any of 100 songs, “Camptown Races“.

The video below wasn’t a fanciful Hollywood mythologizing of the tradition of four-part harmonization; the actors didn’t need to be coached, because they were just exercising the customary cultural habit, that nearly everyone practiced, singing impromptu in groups, a vastly expansive music club rather than a concert. The film clip is an accurate, nostalgic echo of the daily experience of the common people, casually repeated in dozens of old films, portraying the routine habits of legions of real people who once, actively, spontaneously, habitually made quality, casual vocal music as part of their ordinary cultural lives, in the period before the dominance of portable, transistor radios.

(Do you sing at home, or anywhere at all, ever?)

The social, artistic interaction of singers in an ensemble, even the most informal, contrasts vividly with the current experience of “music” through social media. Harmonic singers must listen closely to each other simultaneous with producing their own vocal output, maintaining their place in the key, concentrating on the implied leader, constantly moderating their volume, tempo and timbre, giving way to a temporary soloist or themselves preparing to take the momentary spotlight. (Singing in multiple, harmony parts creates distinct, expressive head-space niches that individual singers could never occupy when singing in unison. ) This constant, dynamic, artistic socialization varies starkly from the social media experience, confined to the sometimes spaghetti-wide aperture into which the internet forces users’ attention.

The “everywhere” ubiquity of transistor radio contributed to the demise of active, musical-cultural life. In the 1960s, people weren’t “Dancing in the Streets” to Martha and the Vandellas, they were just watching “as-seen-on-tv” dance shows, very few stepping up to practice the dance moves. Nineteen-sixties young people were mostly just passively sitting around watching a stilted facsimile of “life” through the little, artificial window pane of t.v., and mindlessly relegating music to the “atmosphere” via the pied piper of the transistor radio. By the 60s, the average person’s actual, living experience of music was more akin to cultural junk-food, elevator-“muzak” as wallpaper background, rather than the active, vital, social-personal emotion of live song universal just a generation prior.

The “everywhere” ubiquity of transistor radio contributed to the demise of active, musical-cultural life. In the 1960s, people weren’t “Dancing in the Streets” to Martha and the Vandellas, they were just watching “as-seen-on-tv” dance shows, very few stepping up to practice the dance moves. Nineteen-sixties young people were mostly just passively sitting around watching a stilted facsimile of “life” through the little, artificial window pane of t.v., and mindlessly relegating music to the “atmosphere” via the pied piper of the transistor radio. By the 60s, the average person’s actual, living experience of music was more akin to cultural junk-food, elevator-“muzak” as wallpaper background, rather than the active, vital, social-personal emotion of live song universal just a generation prior.

“Alexander’s Ragtime Band … published in March 1911 … sold a million and a half copies of sheet music in 18 months.” https://tinyurl.com/yd445b4o

“Until the 1920s, the music business was dominated … by song publishers and big vaudeville and theater concerns. … sheet music consistently outsold records of the same hit songs, proving that most of the music heard in homes and in public back then was played by people, not record players. A hit song’s sheet music often sold in the millions between 1910 and 1920. Recorded versions of these songs were at first just seen as a way to promote the sheet music, and were usually released only after sheet music sales began falling.” https://bit.ly/2Obj5gt Between 1900 and 1909, nearly one hundred of the Tin Pan Alley songs had sold more than one million copies of sheet music. https://tinyurl.com/yej3m982

A short generation earlier, there was a day-vs-night difference in the culture: As late as the start of World War II, most homes didn’t have radio, any more than most homes had television a decade later. But very many, perhaps most homes did have a piano; and they were played, by at least one family member. They weren’t gathering dust unused in the living-room, they were a vital part of the center of family and social life. Prior to the introduction of radio in 1923, phono records were an expensive novelty, hit songs were propagated through vigorous sheet music sales linked to the example of illustrated songs, off-Broadway and operatic singing stars’ live performances, or recordings displayed at music stores. Popular sheet music titles commonly sold upwards of a million copies in the decade of 1910-1919, to be actively performed by many millions of people more.

Without Popular and Folk Music, There Can Be No Art Music. Yes, the music was commercial, a marketed culture. Rigid, purist theorists note that, since broadsheets in 18th century England, the people weren’t singing “true” folk music. But of first importance was the active character of the common people’s practice of music culture, vital for creative synergy to circulate between between popular music, folk music and art music.

Without Popular and Folk Music, There Can Be No Art Music. Yes, the music was commercial, a marketed culture. Rigid, purist theorists note that, since broadsheets in 18th century England, the people weren’t singing “true” folk music. But of first importance was the active character of the common people’s practice of music culture, vital for creative synergy to circulate between between popular music, folk music and art music.

Anthropological-musicologist Curt Sachs noted that, because of culture-suppression against common music in the 17th century English religious revolution, and the consequent impoverishment of base culture, there would be no native born, major English “classical” composer between the death of Henry Purcell in 1695 and the rise of Edward Elgar in 1899, the foreign importation of Handel and Haydn notwithstanding; this, of course, would be news to Thomas Arne and Charles Avison. (Lord of the Rings author J.R.R. Tolkien noted the same effect on traditional English story lore: There is no English mythic tradition, Tolkien declared, so he had to resort to the Finnish Kalavala for his “Elvish” lore, even though that work was only composed in the 19th century.) There is a similar effect today from the technologically augmented suppression of active musical culture, of any quality level. A genius of ages, a musical Dante, Leonardo or Newton, rising in this non-singing culture, would go unrecognized. The vital cultural wellspring dries up as the common people’s voices are stilled. ^Top

Before Radio (1923), If You Wanted Music, You Made It Yourself

Maxwellton’s braes are bonnie,

Where early fa’s the dew,

And ’twas there that Annie Laurie

Gave me her promise true.

Gave me her promise true,

Which ne’er forgot will be,

And for bonnie Annie Laurie,

I would lay me doon and dee.

“But ‘Johnny Nolan’ in the Tree Grows in Brooklyn video clip, was not performing 4-parts, he was faking.” Yes, well and true. Faking is an essential resource in the keyboardist’s toolbox. Johnny was not leading a chorus, he was extemporizing a solo. But most social, group singing of the time was in multiple parts, as part of the common people’s everyday practice of their generally high level of culture.(Tragic Johnny–needing to be a star in a world flush with 1st person musical talent–his keyboard faking took the place of an anticipated chorus of song partners in a social setting; in a live setting it would be taken for granted that the chorus would fill in, if not push out the “fake”–in reality, even a casual accompanist would be expected to resort to the ever present sheet music–because full music literacy was the norm.) A Tree Grows in Brooklyn is about a family so poor the children’s growth was stunted for lack of food–yet they had a piano, trading scarce food to an equally poor piano teacher for lessons. “Annie Laurie” is one of some 200 or so songs that the average person would know, not just to fake “la-la-la”, but know to sing at least the first verse–having done so many times, as a living pastime. This starvation-poor family could only afford 2 books, the Bible and the complete Shakespeare, which they repeatedly read, from one end to the other, over the course of more than a decade–a high-faith and fine-literature orientation virtually universal among the common people, prior to the planned elimination of faith- and classics-based education by John Dewey and William Kilpatrick at the early 20th century Columbia Teachers College.

My mother, father, sister and grandparents in 1938,

before the motorcar broke up families, neighborhoods and coherent societies.

In the generation before radio, there were 100 piano manufacturies in the U.S. alone, to meet constant demand of ordinary families for pianos to be used in their active singing lives, at their cultural center, in the absence of canned music. (Now there are perhaps five domestic U.S. piano manufacturers, only serving an elite trade.) For leisure during the 1910s, my family would go to sing at their cousins in Chicago, where my Mother learned to sing almost before she could speak. Before radio, if you wanted music, you had to make it yourself; passive listeners would invariably be drawn into the active singing. (Nowadays, most people, having been discouraged from singing in childhood, can’t.) This fundamental fact, sharply divides us from all previous history. They sang. We don’t.

You didn’t get lessons or take a degree to learn to sing home music, you learned it at your Mother’s knee.Home music didn’t have to be taught in a class or learned from lessons, it was something you did from your youngest childhood, a part of your family’s traditions, daily life, like having dinner, doing housework or family prayer.

A people who owned such a robust, authentic culture, would never have accepted the vapid church service music we passively tolerate. They sang it; they chose it. We are mere victims of the inane church music that is foisted upon us.

This active cultural legacy was the age-old pattern throughout all human history, prior to the technological impoverishment of cultural life which is ubiquitous today.

The standard history of an alto mandolin, the cittern, shows that in Renaissance barbershops, a musical instrument was commonly present which waiting patrons could tune up to accompany casual choral singing. Video, Renaissance cittern music performance

We have allowed the mere possession of gadgets to supplant a vital personal culture.In today’s technologically enforced, cultural desert, in which we allow the mere possession of gadgets to supplant personal culture, our contemporaries can’t begin to imagine the high level of the everyday person’s real, personal culture just 100 years ago. John Senior, of the Thousand Good Books, estimated that the average person was able to sing 200 songs in the period prior to radio, MTV and continual cell-phone music streaming.

Hundreds of people there were outside. The choir came up in a crowd and I could hear them singing as they walked up the Hill, beautiful indeed. Everybody joined in the hymn, the girls cooking out in the back, and Bronwen and Angharad and the others with me in the kitchen, and my aunts and uncles in the front room, and the women upstairs hanging the last curtains. Everywhere was singing, all over the house was singing, and outside the house was alive with singing, and the very air was song. – How Green Was My Valley

^Top

The Natural, Fervent Love of Tradition

The Music Department Night-Secretary Had a Strong Emotional Reaction to the Exception of Hearing the Performance of Traditional, Common-Practice Period Music, Revealing Something Significant about the Natural, Greater Yearning for Tradition.

In January, 2017, I heard an orchestral piece by Leo Delibes, interpreting a Renaissance vocal piece, Belle Qui Tiens Ma Vie. I applied the music to a 700 year old prayer, Soul of Christ, Sanctify Me.

Bill Keevers playing and singing his arrangement of Anima Christi.

I needed to play the four-part keyboard arrangement on an acoustic piano. In April 2017, I sneaked into a piano practice room at a Northern California college, music department. The department secretary’s strong reaction to hearing the music occurred in the context of the ambient hallway noise, from students “practicing” in the piano booths, largely just incoherent noise, demonstrating the limitations of the poor music to which most junior college students are exposed, their limited cultural experience, unknowingly trying actually to find their tradition, without the firm backing of traditional culture to give them a foundation.

The music department secretary started up, running out of the office, chasing after me out of the building, crying, at hearing traditional music played.

As I departed the music building, the secretary started, impulsively running after me, with tears in her eyes, having been sentenced to perhaps years of listening, night after night, to the ambient cacophony produced by young people, trapped in their pop music ghettos, bereft of an authentic tradition.

This common reaction, love craving of great tradition tends to give lie to the idea that the cultural revolution of the past 50 years was really, sincerely motivated by the desire to jettison “dead, old tradition”, to allow space for “freshness” and “originality”—characteristics that have always been prominent in the great music periods of the past and in the wide breadth of traditional music cultures worldwide today.

A famous soldier, Colonel Gregory R. “Pappy” Boyington, was held prisoner by soldiers of the Empire of Japan in World War II. Prisoners’ diets were deficient in basic fats. Boyington was once unsupervised for a moment in the camp kitchen, where he found what we would call a “rendering container” of what amounts to, lard. He scooped handfuls of, in effect, bacon grease into his mouth, to satisfy an intense bodily craving for lipids. The love craving of traditional cultural music can be most directly compared to the effects of starvation, not on the body, but upon the soul.

The reader might share this basic reaction, love craving of great tradition, as with the “Italiana” of Respighi’s Ancient Airs and Dances, number 3.

A participant in living tradition, Respighi didn’t “originally” compose the pieces of Ancient Airs and Dances; he was an expert researcher ferreting out forgotten music gems from obscure manuscripts lying buried in libraries, tradition transmitted through literacy rather than word of mouth. Respighi rearranged lost, forgotten, traditional music in dynamic, new configurations. As traditionally refreshing is Joaquin Rodrigo’s reworking of a music culture received and passed on by Gaspar Sanz, in Fantasia para un Gentilhombre.

And the reader might have a similar reaction, love craving of great tradition, to Elizabethan composer Anthony Holborne’s Muy Linda. Despite the intensity of the syncopation, the musical structure is not distinct from the scope of vocal harmony, in this case, 5-part. The music is perfectly singable. In fact, Renaissance composers commonly had little instrumental music conception really separate from vocal music. Yet vocalists would have been perfectly comfortable with this highly rhythmic music, contrary to the general trend of simplified contemporary guitar music in church.

The revolution in worship music, “progressive vs. traditional”, allied with the revolution in popular music of the 1950s and 60s, was touted as “throwing out the old and bringing in the new”. Do these young people seem particularly deprived for playing 400 year old music? Does this music seem particularly “crusty & dusty”?

Likewise is the vocal orientation of the music of the qanun–after the Greek word “canon”, for a musical tuning scale. It has a primary vocal structural orientation despite the rhythmic brilliance of the instrument. Nothing played here is unable to be sung. (The short explosions of vigorous sound, seem to be at the place for the “chorus” to sing out, backing up the model vocal “soloist”.) The greatness of authentic, traditional culture, symbiotic between instrumental and vocal orientations, would be more fully available to young people to be heard world-wide, if only our education were up to par for us to experience it.

…Once wily Odysseus had flexed the great bow and checked it all over, he strung it easily, as a man skilled in song and the lyre stretches a new string onto its leather tuning strap, fixing the twisted sheep-gut at either end. Then grasping the bow in his right hand, he plucked the string that sang sweetly to his touch with the sound of a swallow’s note. The Suitors were mortified, and their faces were drained of colour, while Zeus sounded a peal of thunder as a sign. Noble long-suffering Odysseus was pleased at this omen from the son of devious Cronos, and he picked up the feathered arrow that lay alone on the table next to him, while the others the Achaeans were destined to feel were still packed in their hollow quiver. He set it against the bridge of the bow, drew back the notched arrow with the string, and still seated in his chair let fly with a sure aim. The bronze-weighted shaft flew through the handle hole of every axe from first to last without fail, sped clean through and out at the end.A plausible theory to give a context for tradition was developed by Milman Parry and Alfred Lord, to account for the composite character of the Homeric Epic Poems in the original Greek. (Literary analysis seems to point to multiple authors; the Homeric poet seems to be spinning a tale of layered texture.) Parry and Lord attempted to explain the stylistic heterogeneity, by taking the living example of early 20th century Serbo-Croatian improvisatory, oral poets, an ongoing culture practiced in the venue of the Turkish cultural-milieu coffeehouse. Working in a poetic scope with very strict literary rules, poetic lines were divided either into 22 and 23 syllables, or the reverse, 23 and 22, so that there were only two ways to express any particular literary motif, such as “The Sultan’s white horse”. Once each poetic theme and its variant were accepted and established, they became the perpetual legacy of future generations of improvising poets, a complex mosaic of tradition extended over a vast scope of time rather than just the aggregate of the solo efforts of isolated individuals.

An experienced, expert poet would possess a decades-long repository of hundreds of thousands, upwards of a million of these poetic formulas. The essence of the poets’ improvisatory art consisted largely of recombining these long-established, traditional phrases in original, dynamic recitations, woven in immediate time from a larger fabric too extensive and complex to be completely written out. But the formulary building blocks themselves were unlikely to be “original”–their esthetic vigor was in the fact that they were traditional.

Even a peerless improvisor like Art Tatum could be presumed to have personally originated only a small proportion of his grand arsenal of improvisatory riffs; his main forte would be to have accumulated a vast memory bank of formulary phrases, able to produce them at his own command within the improvisational flow in original and dynamic combinations. (Cf. Jazz Musicians and South Slavic Oral Epic Bards)

In the Star Trek, the Next Generation episode Darmok, Picard must either communicate using metaphors based on the names of heroes in epics, or he must fight an alien commander.

Young people 150 years ago lacked the alienation their descendants now suffer, cut off from their family and social traditions.Our traditions make our culture more broadly based in time, able to benefit from experience greater than just that of our contemporaries. Because the common people’s now-disappeared culture was centered in the leisure phase of their everyday lives, it’s worthwhile to consider the normal pattern of traditions in young people’s more-prosaic work lives: Prior to industrialization, it was customary for young people to take an at-home apprenticeship in their parents’ own vocations, learning the tradition of work in the act of doing it, with none of the rigid, age-peer segregation of the period of factory regimentation in education and first work experience. There wasn’t the alienation that young people cut off from their family and social traditions, universally face today. They knew who they were from intimate, everyday experience.

It’s a shame to consider now how the natural yearning for depth and originality in inspirational materials among young people, is strained by the lack of exposure to the great musical ideas of the breadth of world cultures and the long generations of traditions. They are like the man fighting himself in the Room full of Mirrors (Jimmy Hendrix).

Bruce Lee, “House of Mirrors”, Enter the Dragon (1973)

Young people whose scope of “tradition” is limited, tired recycling of the past 50 years, to little music beyond that of the Rolling Stones, can’t avail themselves of the mere idea of exploring the truly deep, African-American music tradition that rock music only parodies. ^Top

Fallout of the Cultural Nuclear Winter

Just as most school teachers by the time of Why Johnny Can’t Read (1955) were incapable of teaching Western culture 30 years after John Dewey had lobotomized education at Columbia Teacher’s College, most keyboardists are no longer capable of following a sight-read, traditional four-part harmony arrangement. They can only make a cursory, superficial analysis of the chords – possibly erroneous, depending upon the player’s level of musical education – apply a narrow, homogenized, conventionalized routine of faking—in the pejorative sense—the deficiencies of which they can count on the congregation not to notice–because the congregation don’t sing anymore, and are themselves quite unaware of the culture they have lost. Nemo dat quod non habet, “no one gives what they don’t have”.

Most faking practitioners possess only very modest improvisational skills. (It isn’t really “improvisation” at all; top Jazz artists report consciously avoiding ever repeating the particular execution of a performance, out of the sheer boredom that would entail; whereas, faking “music ministers” tend just want to get through it, doing the same inferior job over and over.)

Classic arrangements reflect continual critical filtering and selection of generations of active music practitioners.Traditional four-part arrangements in the best, old hymnals, peaking around the year 1940, used commonly-agreed upon standards of voice-leading anyone familiar with the tradition by habitual singing can practice without extensive, formal training. (The same pertains to the thought of philosopher Thomas Aquinas, whose work at first seems to present a daunting prospect, because of seeming mathematical rigor. High School students properly instructed in Aquinas can easily master the concepts, unlike the relatively incoherent philosophy that succeeds Descartes.) Master arrangers and composers were capable of setting the higher-level organization of voices enjoying their intelligent integrity and yet blending overtones in succulent harmony. The typical faking “improvisor” has nowhere the compositional or improvisatory acuity of a member of a fine tradition at high pitch, not to mention the blinding light of a master of ages such as Josquin des Pres or Sebastian Bach. Extreme masterworks enter tradition at the top of the lists, memorized as the core fabric of countless singers’ visceral tradition. (Thanks to no small historical accident, but due to the genius of a traditional culture, the music of JS Bach has thoroughly ensconced itself in the Afro-European tradition of Brazilian music, as with this Air on the G String in a Samba rhythm.) A keyboard faker, with diminished ability and perhaps no inclination to follow the voice-leading practice that is the heart’s home of vocalists, can only travestize the name of the Art of Music.

The specific arrangements reflect continual critical filtering and selection of generations of active music practitioners, who as cultured amateurs were yet highly capable of mounting sophisticated, worshipful music performances to adorn the Drama of Calvary, based on tried and tested arrangements.

The proper place of faking is between composing and improvising, closer to the latter. An example of the process of improvisation moving into composition, is with Beethoven’s excellent piano sonatas, as an outgrowth of his customary practice of progressive-traditional keyboard improvisation as a first-rank pianist. After attaining a high pitch of performance, improvising on new and original themes, those extemporaneous improvisations would become crystallized and polished as formal compositions–in the same field of play as the minor masterworks in the best church hymnals, which went through the same process. But all composers had first undergone a thorough music education–the very thing lacking in church music fakers.

We can see an example of “faking” which is thoroughly improvisatory, on the part of a contemporary master, Netherlands Antilles composer Wim Statius Muller. (This is the informal national anthem of the tiny Caribbean country of some 800,000 souls.) As he accompanies a singer, his “faking fill-in” has much of the quality of his regular compositions, and could be transcribed and published as a modern classic with only a little editing, expanding on the fill-in at which he reverts to street polyrhythms.

Despite best intentions, the present generation of faking musicians simply, generally lack minimal technical competence to perform four-part singing and accompaniment; most choir members today haven’t the faintest conception of what great vocal harmonization sounds like.

The Rise, Fall and Decay of Intricate Harmonic Virtuosity

The oversimplification of contemporary, faked music relates as a shadow to its substance, to the period of common practice 1450-1950. In the middle ages, the ideal in interactive multi-part singing was for each voice to have independence, the ability to stand on its own and maintain interest for each singer, even as each voice maintained coherent relation to the other voices.

I Am Here, Sir Christhismas – Dieu Vous Garde

As a new organizing scheme of perspective sprang up in the early Renaissance, a parallel movement towards the harmony we recognize came up under the name of fauxbourdon.

The voices don’t move in rigid parallel, but multiple rhythmic paths maintain their own distinctiveness within the harmonic perspective. By the late Renaissance, this polyphonic complexity started to become more-nearly simplified into the parallel-rhythmic “block-chords” of homophony, but the distinctness of the voices’ identity was always beckoning from the tradition’s long memory.

Harmonic polyphony would maintain the older, medieval ideal of the integrity and interrelation of distinct voices, arranged in the new harmonic perspective. Each voice moving with intelligence as it related to the master harmony, remained the ideal throughout the Renaissance, and was carried over, without ever being quite lost, as instrumental intensity increased during the Baroque.

But each good thing that arises has its dawn, noon and sunset. So the ideal of the intelligent integrity of individual voices began its slow wane in the Classic and Romantic periods, the subordinate voices coming increasingly to be relegated to the background as partially static props which derived meaning only in reference to the solo line, the now inessential, subordinate melodic lines sometimes given nicknames like “noodling”. No longer was each part capable of expressing a complete musical idea on its own, only the solo line. It was finally in the 1960s folk-popular music revolution that the recently deceased cultural body would begin its rapid biochemical breakdown in the moments succeeding death, as keyboard faking and overly simplistic guitar music reduced melody to idiocy. ^Top

The Dagger in the Heart of Harmony

The Dagger in the Heart of Harmony

Hymnal publication operations today must prominently feature guitar editions as their standard. (Episcopal Church Publishing Guitar Edition.) But when the very best hymnals were compiled, around 1940, after decades of refinement since the 1906 English Hymnal, there were no guitar editions.

When Hymnals were at their peak of quality, there were no Guitar Editions.

C.S. Lewis had remarked on the cause of his fall into atheism, as partially attributable to being forced to sing inferior hymns at school based on “fifth-rate poems set to sixth-rate music“. The compilation of The English Hymnal by Ralph Vaughan Williams was in part, reaction to long impoverishment of song, so extensive that many churchgoers had never even had the experience of singing in church during their whole lives.

The dominance of faking and decline of harmony, seem to have been involved with the incursion of less highly cultivated guitar music into the heart of church vocal practice. The history of western popular music from the 1960s shows the beginnings of this trend. Ernest Gold’s Oscar-winning Theme from Exodus (1960) was dressed up in orchestral clothes. But upon harmonic analysis, the Exodus theme is revealed to be fundamentally a folk-guitar composition, perhaps authentic in view of the presumed use of guitar in the kibbutz movement. In contrast, the attentive ear may be able to detect traditional four-part harmony as underlying Jerome Moross’s 1958 Oscar-nominated theme from The Big County.

The dominance of faking and decline of harmony, seem to have been involved with the incursion of less highly cultivated guitar music into the heart of church vocal practice. The history of western popular music from the 1960s shows the beginnings of this trend. Ernest Gold’s Oscar-winning Theme from Exodus (1960) was dressed up in orchestral clothes. But upon harmonic analysis, the Exodus theme is revealed to be fundamentally a folk-guitar composition, perhaps authentic in view of the presumed use of guitar in the kibbutz movement. In contrast, the attentive ear may be able to detect traditional four-part harmony as underlying Jerome Moross’s 1958 Oscar-nominated theme from The Big County.

Enrique Granados’ Oriental seems to have been pianistic in its composition, but it can be interpreted equally well on guitars. Pernambuco’s Sound of Bells is more fundamentally a guitar composition, with virtually no vocal applicability; it can come off poorly on piano mostly because of the habit of customarily, overly imbuing piano interpretation with the speeding-up and slowing-down of rubato, which interferes with this guitar-rhythmic conception. (Even so, a little rubato is written into the music.) But even a Malagueña, more customarily played on guitar, can be properly executed on piano.

Music of the guitar’s immediate predecessors was commonly voice scaled. Renaissance lute music maintained much closer compatibility with cultivated vocal music than recent, folk and popular guitar music has. The music of the Arabic oud, a more remote historical predecessor of the guitar, centers on the ideal of vocal text, even when the oud is played in an instrumental solo. Music improvised on a mechanical instrument, rather than voice, can delve into fancies to which the voice on its own would not easily tend, nor steps ever dance to; but the connection with the vivid immediacy of the “instrument” built into the person–the voice–is never lost in older traditions.

The best guitar playing is not necessarily any less virtuosic than other types of instrumental practice. But such good quality guitar music isn’t very compatible with church music, which should primarily give voice to a text, it develops instrumentalism beyond the limits of vocal music. And the overly simplistic folk and popular types of guitar music played in the churches today can’t support the best text-based vocal writing. In fact, today’s genre of popular guitar playing necessarily diminishes the quality of vocal music, below the more highly cultivated standard that was maintained in churches prior to folk and popular music movements beginning in the 1950s.

The primary result of the spread of folk-popular guitar music in our time has been to degrade the virtuosity of vocal practice.The net result of the spread of guitar music in our time has been to degrade the overall virtuosity of vocal practice. The proliferation of cheap guitar music, which has spread into churches, occurred in the broader social context of the spread of commercial, “pop” youth-culture music mass-marketed for an age-segregated audience, eroding the inheritance of prior generations’ own vigorous vocal culture. (In the bravest, early days of the social revolution, you could plop down $25, buy yourself a guitar, learn to play three chords, and you could proceed to irritate your parents with “your own music”. Translated to church, this was touted as being the cultural foundation for an original renewal of the Christian faith, jettisoning the encumbrances of centuries of old tradition.)

It is arguable that the nearly exclusive adoption of keyboard faking, specially occurred in the historical context of the predomination of overly simplified guitar music in so much of our worship practice. It is prejudicial to regard the guitar as an inherently inferior instrument; but a valid common factor in the decay of our musical culture does fairly seem to be the degradation of music literacy and rudimentary education.

In balancing the development of instrumentalism against the cultivation of vocal music, judgments about the “new music” should be subject to the consideration, whether or not the kernal conception of church music should be centered on the vocalization of a text, or should the fundamentally mechanical character of musical instruments be allowed to overpower and degrade the human scale of word vocalization. The result of failing to examine these issues, has often been that new music practitioner just twangs away while voice-lines become ever simpler, the loss in vocal virtuosity escaping notice of the congregations and the new musicians themselves.

We face special challenges from inherently rhythmic guitar in this era of conscious, inartful simplification of music. The subtler rhythms of vocal text tend to face cultural extinction under the coarse rhythmic noise of so much folk-guitar playing. This is not the case with the rhythmic music of the Arabic oud, Persian tar, and similar families of instruments of the Indian subcontinent, The excessively mechanistic-rhythmic character of today’s common practice of guitar music has been allowed to ride roughshod over the human-scaled, vocal character our music has had since its origin.despite those instruments’ superficial, mechanical-structural similarities with the guitar. It is not the mechanical structure of stringed instruments that is at issue, it is the music that is played on the guitar that has become fundamentally degraded in the contemporary post-modern West. Guitar vocal music has become divorced from its own, fundamental vocal conception, increasingly adhering to the simplistic musical standard to which common folk and popular guitar playing is limited. Whereas, the music of traditional eastern rhythmic string instruments is not alienated from the unrestrained intricacies of the music of the voice. Oud, tar and sitar, serve the humanity of the voice and shadow its intricacies, rather than reducing culture by dominating the voice because of the degradation of some historically dead-end, decadent instrumental technique.

Tradition continues its relentless march, past the wreckage of the once-great, former Western civilization, as we can note with a genre which has arisen since the time of dead-end, Western hootenany music in the late 1950s, the practice of fretless classical guitar music, called perdesiz gitar in Turkish, always retaining its original, voice orientation. It is sometimes electrified, innovating progressive-traditional, voice-modeled music in microtonal scale. Turkish public coffeehouse music shows this consonance of stringed-instruments with the voice, respecting the limits of the voice’s range, its tessitura. (Notice anything? Everyone in the place is singing.)

This music is in the maqaam (mode) “Taksim”, somewhat like an ancient European modal scale, but actually, a full-blooded melodic pattern as the foundation for traditional-improvisation, analogous to Malagueña or La Folia in the west.

Tradition continues its progress unabated on some of the margins of the old Western civilization. In the Caribbean Netherlands, a composer melds the vibrant, polyrhythmic regional folk culture with the art music inheritance of Chopin.

But in the heart of the cultural shadowlands, with the over-simplification Western guitar music in the core of the former Western civilization, beginning with the folk-music period of the 1950s, the overall influence of guitar music and keyboard faking on our worship has indisputably been to degrade the once fine intricacy of the music held close to our hearts, lowering our own receptivity to true greatness. As with the music of Ludovico Einaudi; it may be loved by a people who were raised in an environment of fundamental cultural deprivation, but the future will bypass any notice of such a negligible parody of true culture. It may be orchestral, but it’s not classical.

Ecce Homo: Rather than restoring the priceless old cultural tradition adorning Christ’s unique sacrifice of Himself on the Cross of Calvary, instead, mutilating the Imago Dei through music.

Banality Critiques Its Betters

Active choral congregations didn’t have to wait for contemporary fashionable, “progressive” choral music to develop, to maintain vigorous enthusiasm for their music. They had always entertained zeal for the music that they practiced. They weren’t merely waiting passively for oftentimes poorly educated “music ministers” to serve up their enthusiasm to them.

The whole history of music since prior to 1450 had been marked by series of milestones of progressive innovations. The churches accepted and fostered these stylistic innovations, so long as they could be sanctioned as sufficient in reverence to enter into worship services. But during all that long stretch of development and innovation, there was no mania to shun older forms, even when a new fashion was accepted and supplanted the style of a prior period.

All “classics” start as terrific popular entertainment, and attain their classic designation by possession of multi-dimensional depth which contemporary audiences may not at first perceive.The recent folk-guitar and faking movement deliberately rejected the seeming academic basis for study of great, old music innovations. All “classics” start as terrific popular entertainment, and attain their classic designation by virtue of singular works of unique quality possessing multi-dimensional depth which contemporary audiences may not at first perceive. (Among the best: play, Hamlet Prince of Denmark; novel, Brothers Karamazov; music, Goldberg Variations.)

Today’s guitar compositions are necessarily limited by the inability of guitarists to support choral singers with the fuller range and flexibility of movement of the keyboard, the inevitable tradeoff for the guitar’s structural simplicity and the decline of our popular music below a certain standard of cultivation. Folk guitarists seldom fully utilize even such technical capabilities as the guitar does possess, usually keeping to simpler chords in the first position by the nut, seldom venturing into more complex melodic movement in sympathy with the voice; this poverty of technique necessarily feeds back to poverty of choices in vocal text line composition and interpretation.

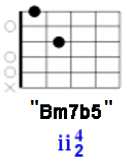

An example of making old simplicity newly complicated, is a chord used in O Come, O Come Emmanuel–on the second syllable of the word “Israel”–and in the prayer of Theresa of Avila, Nada Te Turbe (“Do Not Be Disturbed”, don’t be afraid), on the words “tiene” and “Dios”. A natural diatonic chord, in the second step of the natural minor mode, a B diminished in the third inversion (7th in the chord bass), one of the easiest chords to play on folk guitar, has to be mutilated by OCP to be a iv6th, minor four-step 6th chord out of the diatonic schema in order not to cause discomfort to folk guitarists. However, when the chord is properly used, Jazz theory has to strain at a gnat and call the simple diatonic 7th chord a “minor 7th with flat 5th”.

The guitar fretboard could be made to play melodic lines compatible with the natural preferences of the voice, as does the fretless oud; but guitarists tend to digress off into their own idiosyncratic folk and popular playing technique, veering away into forgetfulness about what should be the fundamental centrality of the vocalization of verbal texts, as they were once fully realized in the “old, traditional” vocal practice.

The poverty of folk-guitarists’ idiosyncratic playing technique necessarily feeds back to poverty of choices in voice lines. The guitar fretboard could be made to play intricate melodic vocal lines. But guitarists tend to digress off into their own self-absorption, away from the fundamental centrality of the voice.

When adding keyboard to the mix of contemporary-popular and folk instruments, faking undercuts much of the historical advantage of keyboard support for the voice. Much of the music now composed even with keyboard assistance, has been contaminated with the self-hobbling limitations of the folk-guitar culture, as it dominates much of contemporary church music.

Even an older hymn, Come Holy Ghost, is very difficult to place into a satisfactory, harmony arrangement, because the melody is so simplistic, as if the tune were composed by a folk guitarist a century or so past. (Indeed, Silent Night/Stille Nacht, is known to have been composed on guitar, and is unlikely to be put into an arrangement of any particular complexity; while that may be a charming effect, to signify the poverty of Christ’s birth, that level of simplicity can’t prevail over all worship music.) When oversimplified guitar compositions are artificially expanded to multi-part arrangements, the inartful, excessive simplicity of the lead line, meaninglessly bloated out to additional parts, is only made the more apparent, making a silk purse out of a sow’s ear. (Example: Purify My Heart, written-out fake “lead” sheet Audio. Sheet music.)

Ralph Vaughan William’s Down Ampney is much superior to Come Holy Ghost

An accompanying issue is an animal reaction to this unconscious weakness, overcompensation in the form of inartful, needless complication in vocal text lines—without true intricacy. After 1970, uncultured Broadway show-style music became the staple of new, church music. A young father recently commented on about “banal modern liturgical music more suitable to failed off-Broadway theater”.

Low grade, inartful vocal acrobatics in an uncultured, Broadway-show genre, seem calculated to exclude congregations’ participation in singing.

It is hard to argue that this melodic ineptitude was not calculated to exclude congregations, making choirs the worship service’s “music specialists”, however unqualified they may now be to sing truly cultivated music. The choir were now carrying on singing low-grade vocal acrobatics, in a meaningless cultural maze, in which the average congregation member, who had once sung vigorously, could never participate.

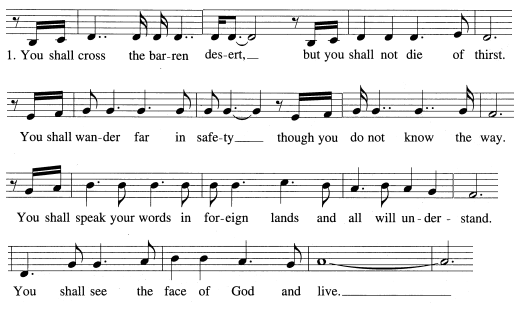

For example, the verse from a well-known church song, Be Not Afraid, turning the Lord Jesus’ strict censure against failure to exercise the virtues of courage and fortitude (“O ye of little faith” Matthew 8:26) into maudlin sentimentality. The music is punctuated by meaningless rhythmic elaboration that would only make sense if ministers processing into the service were to pause walking in at every rhythmic stop–the image that the music evokes in the mind is ridiculous, like the Monty Python Ministry of Silly Walks.

For example, the verse from a well-known church song, Be Not Afraid, turning the Lord Jesus’ strict censure against failure to exercise the virtues of courage and fortitude (“O ye of little faith” Matthew 8:26) into maudlin sentimentality. The music is punctuated by meaningless rhythmic elaboration that would only make sense if ministers processing into the service were to pause walking in at every rhythmic stop–the image that the music evokes in the mind is ridiculous, like the Monty Python Ministry of Silly Walks.

This music only came into common use because a publisher pushed it on a non-singing church public, who had forgotten their traditions and lacked the personal experience of home singing to enable them to perceive intuitively, on first hearing, how really bad this music is. Worst of all, the choirs themselves can’t even accurately perform the music that is written on the page, so unvocal and antirythmic, the beat unable ever to be caught, are the sixteenth notes as perceived by commonsense habits of singing. Intense rhythmic syncopation has fine folk tradition precedents, but this harebrained arrhythmia is disconnected from tradition. So the singers are left to their own devices without coherent assistance from composer or publisher to haphazardly interpret the musical directions as best they are able according to their legitimate tradition. Even good musicians cannot follow the clumsy rhythmic schema.

This music only came into common use because a publisher pushed it on a non-singing church public, who had forgotten their traditions and lacked the personal experience of home singing to enable them to perceive intuitively, on first hearing, how really bad this music is. Worst of all, the choirs themselves can’t even accurately perform the music that is written on the page, so unvocal and antirythmic, the beat unable ever to be caught, are the sixteenth notes as perceived by commonsense habits of singing. Intense rhythmic syncopation has fine folk tradition precedents, but this harebrained arrhythmia is disconnected from tradition. So the singers are left to their own devices without coherent assistance from composer or publisher to haphazardly interpret the musical directions as best they are able according to their legitimate tradition. Even good musicians cannot follow the clumsy rhythmic schema.

A book a generation ago roundly condemned the Irish Sweet Song in church music. But Irish Sweet Songs were sung with gusto at home; Irish-Americans had plenty of opportunity to weep and express their sentimentality in its proper setting, with friends and family. Today’s feel-good “modern” church song, sort of macramé in song, is not premised on the solid social setting of a singing society, rather, the people who “love” their post-hippie music generally don’t have any other outlet for experiencing wildly sentimental feelings. But in the church setting, worship isn’t about us, or about our feelings, it’s about God, about awe for his majesty and deep gratitude for his sacrifice of his son on Calvary. There shouldn’t be any tear-jerkers in church. The music should be reverent with self-discipline. Go get your good feelings at home, in a pub or with a community singing group. Leave church for awe for God.

A book a generation ago roundly condemned the Irish Sweet Song in church music. But Irish Sweet Songs were sung with gusto at home; Irish-Americans had plenty of opportunity to weep and express their sentimentality in its proper setting, with friends and family. Today’s feel-good “modern” church song, sort of macramé in song, is not premised on the solid social setting of a singing society, rather, the people who “love” their post-hippie music generally don’t have any other outlet for experiencing wildly sentimental feelings. But in the church setting, worship isn’t about us, or about our feelings, it’s about God, about awe for his majesty and deep gratitude for his sacrifice of his son on Calvary. There shouldn’t be any tear-jerkers in church. The music should be reverent with self-discipline. Go get your good feelings at home, in a pub or with a community singing group. Leave church for awe for God.

Of course there are positive exceptions to the main trend of the barbarization of guitar music. The Seekers’ tribute to fidelity in marriage, I Know I’ll Never Find Another You, is mainly a guitar composition, from an established tradition of guitar-vocal music; but the workable vocal melody is filled in with a good-quality 4-part arrangement, in a fine balance between vocal and instrumental emphases. The Brothers Four’s Green Fields, with sharp vocal harmonies to contrast with the essentially guitaristic approach, is especially poignant in an age with prominent anxiety at the prospect of nuclear annihilation.

But with the main trend of the over-simplification of guitar chords and the homogenization of faked keyboard accompaniment, this cultural breakdown byproduct, bizarro-superman block-head “harmony”, has now reached the point of dissolution like a grave robbing party at 3 AM, forming a hideous parody of the once-living tradition of harmonic vocal music.

These two main developments in the past 50 years, under the technologically hastened leaching of active, authentic culture, the one, overly simplified guitar music that lessens vocal cultivation, and the other, streamlined keyboard faking that only allows a simple, unison melody line to be sung: both main trends occurred at the expense of a once-thriving choral music culture. ^Top

Atomistic Culture – A Fruitless Search for a Viable Contemporary Western Tradition

I sought in vain for a cultured example of music for a prayer composed in 1886.

Unlike the traditional Renaissance music for the ancient prayer, Soul of Christ Sanctify Me/Anima Christi, as cited above, a very popular composition of Anima Christi by Marco Frisina, is essentially in the guitar-folk genre.

There is a tradition of what are called prayers of deliverance, which are amenable to setting to music. Besides Anima Christi, these include St. Patrick’s Breastplate by Sir Charles Villiers Stanford (1889), in the common practice tradition, and the 1886 prayer St. Michael the Archangel, Defend Us in Battle. (Michael the Archangel is mentioned in the bible in 1 Thess 4:16, Daniel 12:1, Jude 1:9, Rev 12:7-9, and Daniel 10:13-21. Scripture studies note that Michael’s name originates in the phrase “who is like God“? A prayer to an angel, which is not the adoration only accorded to God, has the biblical precedence of Luke 1:34-38, “How shall this be, seeing I know not a man?…Behold the handmaid of the Lord; be it unto me according to thy word.”)

In searching for contemporary and historical music for the St. Michael Prayer, I found that the current “tradition” operates at the least common cultural denominator, now prevailing across the expanse of the former Western culture. Practitioners of the contemporary casual music genre approach the task of composition in a nearly complete cultural shadow. In many instances, little or no reference is made in their compositions to any cultivated musical predecessors. The “tradition” on which such music is based, is completely uncultivated, highly idiosyncratic music, as if Jean-Jacques Rousseau had been made cultural commissar, with no reference even to any established traditional folksongs commonly in circulation a century ago, or any popular music that was economically viable.

I call this organizing principle, ⚛cultural atomism ⚛. All that is necessary to begin practicing such music, is to obtain an inexpensive musical instrument, most commonly a guitar, or perhaps an inexpensive keyboard, then to learn a minimum of sub-literate music conventions: simple chords, conventional riffs, and contemporary vocal timbres such as groaning, growling, howling, and a very peculiar timbre I have heard from a faking pianist, a combination of moaning and yodeling that I call “myodling”. The composers of such music perhaps draw some vague reference to music of a dissolute, historically local, commercial-popular tradition, then begin the process of composing unvocal “melodies” from virtually nothing.

I call this organizing principle, ⚛cultural atomism ⚛. All that is necessary to begin practicing such music, is to obtain an inexpensive musical instrument, most commonly a guitar, or perhaps an inexpensive keyboard, then to learn a minimum of sub-literate music conventions: simple chords, conventional riffs, and contemporary vocal timbres such as groaning, growling, howling, and a very peculiar timbre I have heard from a faking pianist, a combination of moaning and yodeling that I call “myodling”. The composers of such music perhaps draw some vague reference to music of a dissolute, historically local, commercial-popular tradition, then begin the process of composing unvocal “melodies” from virtually nothing.